Delft Blauw, Chinese Porcelain: Reading ‘Vermeer’s Hat, Indra’s Net and the Dawn of Globalisation’

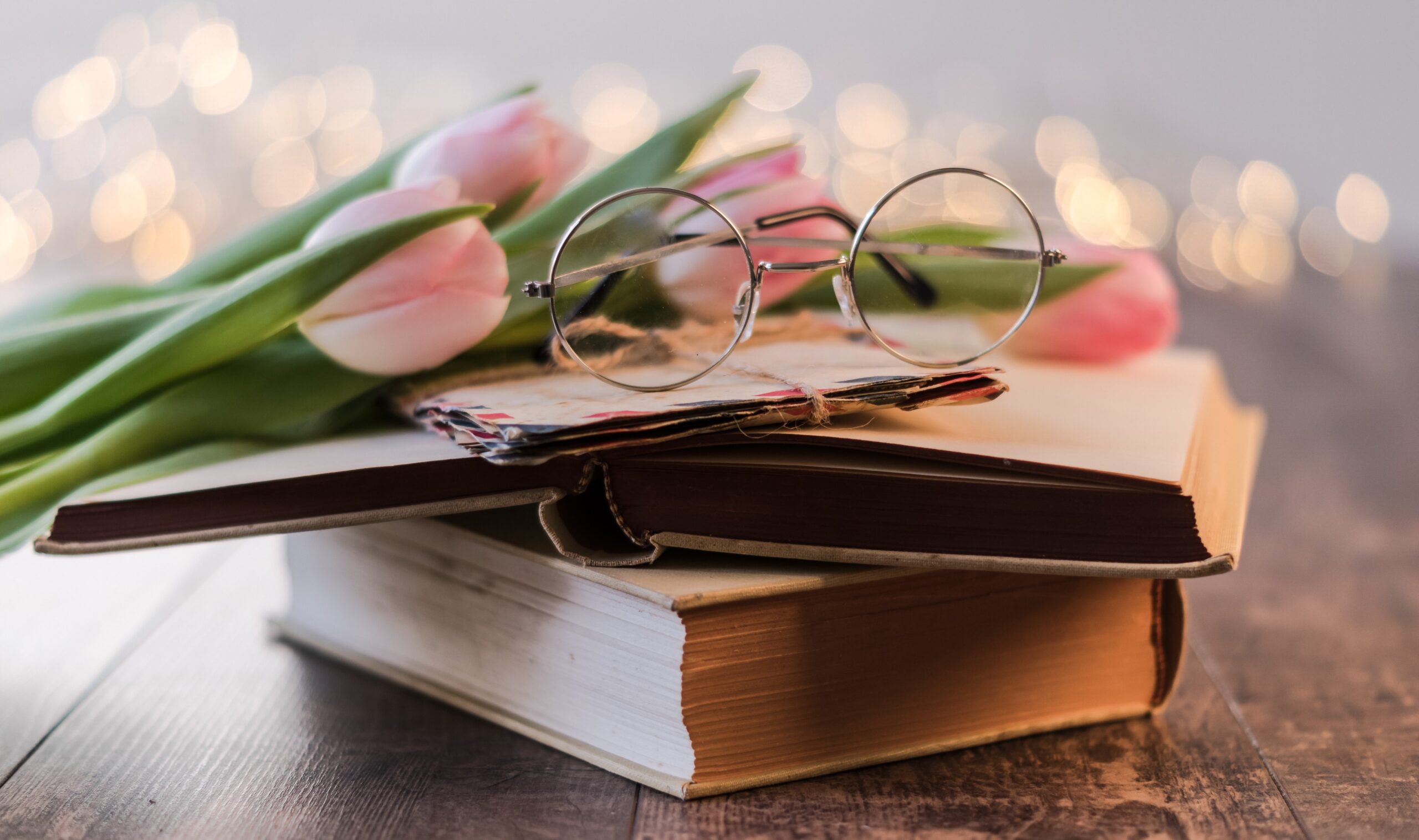

I have a sweet spot for ceramic. On my last day in Amsterdam this year, I chanced upon a souvenir shop near Dam Square selling exquisite blue-and-white Deftware. A few minutes later, I felt fourteen euros lighter and was loaded with two lovely trinkets to take home to my mum in India: a cat that pours milk and an origami-inspired coffee cup. This cup has not only become my favourite piece of drinkware, it is a small part of a larger story that spans centuries and continents, crockery and cultures.

Heinen Delftsblauw in Damrak, Amsterdam

For most of us ignoramuses blue-and-white porcelain screams Dutch as does Gouda cheese. However, a tour of the Amsterdam’s famous Rijksmuseum reveals rooms and rooms of similar pottery (more than 7,000 works); pyramid vases, chipped crockery depicting daily life in China; most of these date back to the 17th century, at the height of the Dutch East India Company (VOC – (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie). Clearly, the faience that has for so long become “native” to the Netherlands was inspired – to use the term loosely – by Chinese porcelain that made its way to wealthier Dutch homes through global trade networks.

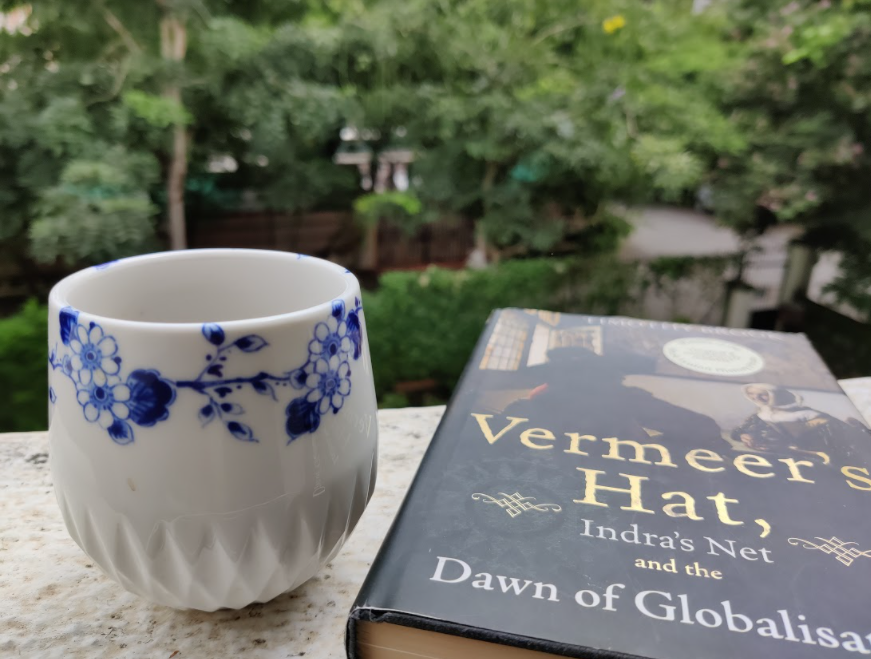

My new favourite coffee cup from the Blauw Vouw collection Romy Kühne X Heinen Delftsblauw

I picked up Timothy Brook’s Vermeer’s Hat, Indra’s Net and the Dawn of Globalisation a few months after my visit to the Rijksmusem. Naturally, I was curious, having seen some of Delftman Johannes Vermeer’s works in the museum’s Gallery of Honour (which houses Rembrandt’s Night Watch) including his most famous Milkmaid and View of Houses in Delft, Known as ‘The Little Street’ among others. Brook employs six of the Delftman’s paintings to string together a narration that goes beyond small Netherlands and an even smaller Delft.

View of Houses in Delft, Known as ‘The Little Street’, Johannes Vermeer, c. 1658

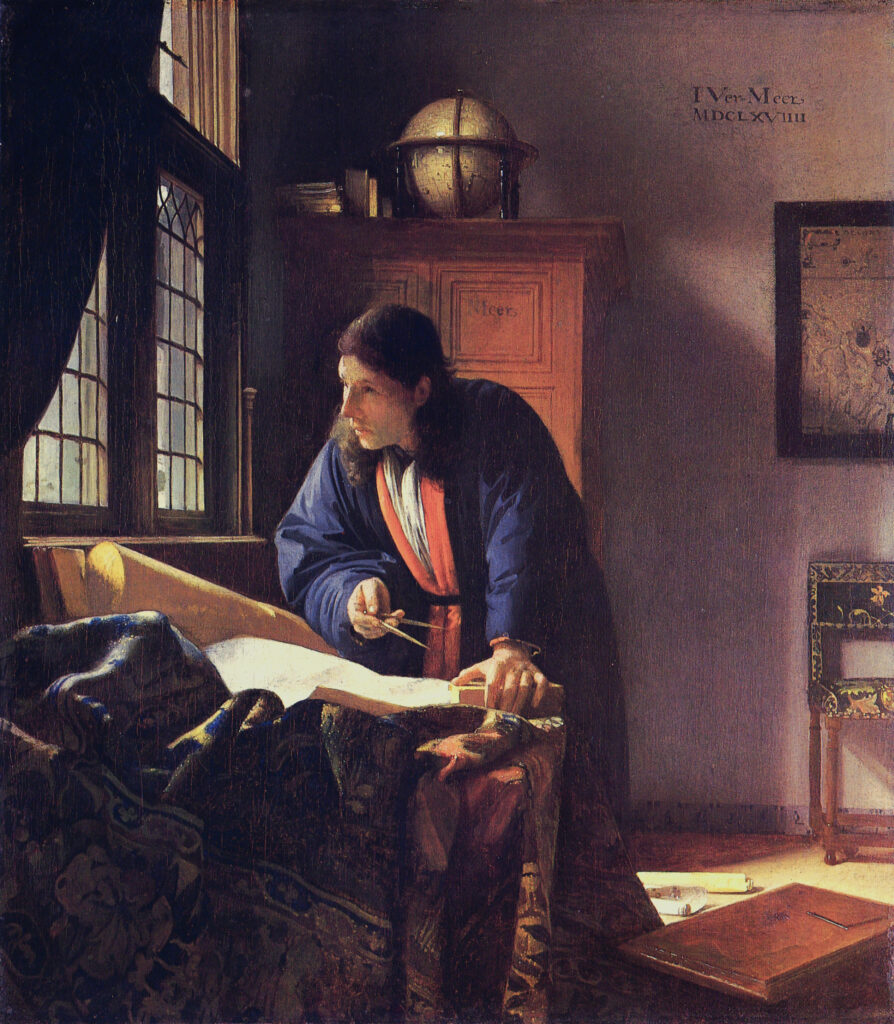

Vermeer had never been outside of the Netherlands so it is quite extraordinary that his paintings display a world beyond his own, one that was rapidly undergoing globalisation, with trade networks spanning expanding from Europe to Asia. Brook states that Vermeer’s paintings show a new model of the 17th century world that was fast globalising – “an unbroken surface on which there was no place that could not be reached, no place that was not implied by every other place”.

Through every window, globe, hat, Turkish rug, earring or soldier seen in Vermeer’s paintings, Brook opens our eyes to the goings-on that were happening far away from the Low Countries, far away from Vermeer but close enough for the maestro to make observations in his baroque paintings famous for depicting domestic life.

Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, Johannes Vermeer, c. 1657-59

Global consciousness, he argues, began with the voyaging of Dutch traders who appear in a manner daredevil-ish – sometimes fighting with their former colonisers, the Spaniards (who were also criss-crossing the globe simultaneously) and accumulating their loot, other times being imprisoned on Chinese soil during their journeys.

The Geographer, Johannes Vermeer, c. 1668-69

It is – now – no wonder to me that the blue-and-white “Delftware” is in fact a pale imitation of its true original, in a manner similar to that of golden tea becoming a global phenomenon – a concoction of turmeric and milk, famously used for curing the common cold, one that all Indian mothers have sworn by for centuries. But even this imitation carries its own history of the shared human experience of travel, culture, craftsmanship and trade.

The book is in many ways a joint effort by a Delftman and a Canadian, separated by centuries. Through painting and prose, Vermeer and Brook weave a multifaceted narrative, connecting 17th century Europe to the world. And it is one that promises to leave you agog.